5.6 Qanat (Kariz) culture - culture of contentment

For centuries, Iranian in drylands have overcome the challenge of water scarcity through methods of water harvesting, called Qanat.

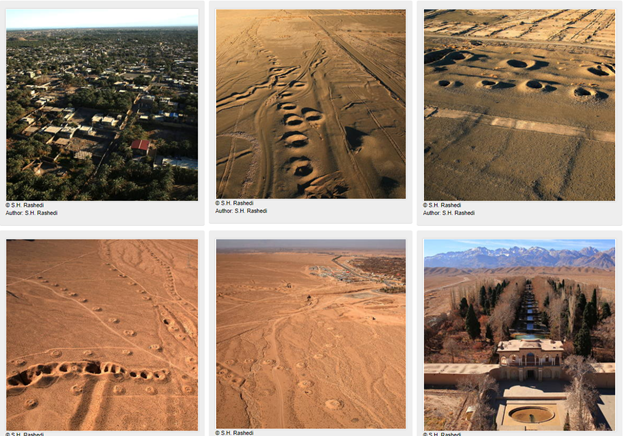

The Persian Qanat (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1506/gallery/&maxrows=21) © S.H. Rashedi

What the recent drought makes clear to those depending on water in the agricultural sector all over the world including the Netherlands?

Agriculture uses far more water than is sustainably available.

How ‘the Maize and Grassland cultivation brought into production in the sandy soil of the eastern part of the NL is far more land than the surface and groundwater have water to supply.

Much of the economy here relies on dairy farming, but with the water supply issues, there is a need to diversify the economy on sectors outside of these crops and animals. Moreover, in the study region due to the lack of water supplies and dryness, farmers should grow crops that required much less water than Maize, Grass, and Potatoes.

It is essential for the Netherlands and Europe to have insights into water management and drought cultural, social, and environmental challenges elsewhere in the world. This post closely links environmental challenges in Iran and Europe. We are aware of the shortcomings/challenges present in the current Dutch and world water issues and bringing indigenous ancient Persian sustainable and collective water harvesting solutions.

The main objectives are:

to highlight the peaceful cultural and social cooperation qanats as environmentally sound water harvesting have provided, so as to preserve the legacy of cooperation they have left the entire world, and learn from that legacy how water, and other scare resources, can be peacefully shared in the future.

to acquaint the reader with technical and social concepts of qanat

to review the geographical studies ever conducted on qanat system in Iran and in the world

to indentify intercultural interactions regarding qanat technology

to examine different aspects of cooperation and social convergence in qanat

to explore historical records and archeological evidence on the geographical diffusion of qanat in world and the role of nations in spreading qanats

Introduction

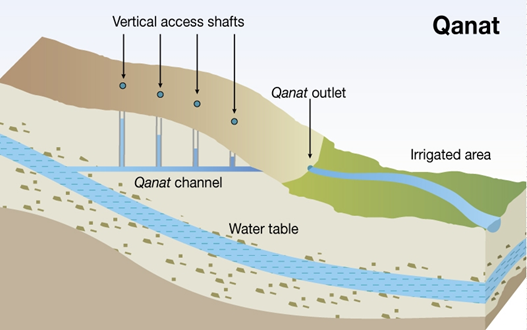

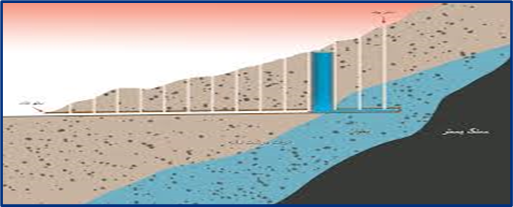

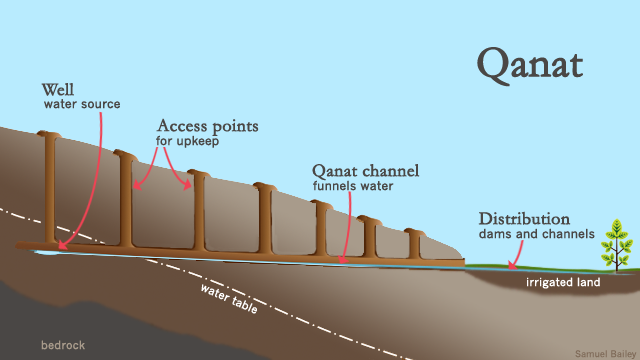

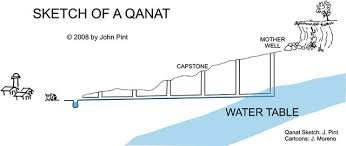

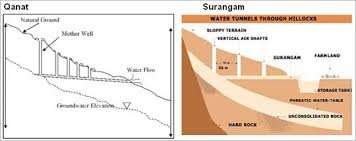

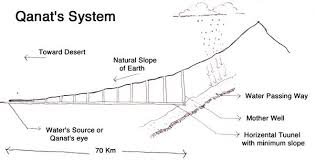

A Qanat is a gently sloping subterranean canal, which taps a water-bearing zone at a higher elevation than cultivated lands. Qanats are environmentally sustainable water harvesting and conveyance techniques through which groundwater can be obtained without causing damage to the tapped aquifer. In the course of history, qanats have been used to meet the demand for water in many arid and semi-arid regions of the world. This technology has given rise to the so-called Qanat Civilization.

The success of the qanats as a sustainable technology to harvest groundwater is impressive and well documented. However qanats are not mere water harvesting and conveyance systems, but social systems that manage water in a sustainable manner. The success of the technological system is thus mirrored by its success as a social system. In a world where water use and conflict are common, the social institutions created allowed for peaceful and cooperative management of water in arid regions of the world. For this reason, the experience of the qanats can provide many valuable lessons regarding the social institutions needed as the world faces increasing scarcity of water.

Qanat system was a sustainable water harvesting approach, to deal with the water challenges in Iran, e.g., water scarcity, safe drinking water and sanitation, water-related hazards and climate change, water and ecosystems quality, water management and governance, and food security.

It is obvious that water harvesting would be defined differently under different climatic conditions, hence distinctions should be made between harvesting methods under (semi-)arid, sub-humid and so on. Obviously it is not the purpose to advocate excavating qanats in NL, but considering the impact of climate change that has led to the drop of groundwater table depth( in NL and, and in many other places worldwide).

What is really the underlying issue when hearing the name “Qanat”, is related to the social aspects of it, which were ever sustainable in the past.

The curious case of Qanat as an initial idea for this project has so much through such construction. The present Qanat situation demands us to feel not only for the death of nature we witness, but for the incredible life and civilization we discover. It prays on the obvious morality of human societies but also dangles the idea in front of us why not sustainable anymore, just not in the same way was in the past.

Throughout centuries of Qanat life story, makes sustainability who ages backwards. After so much anticipation we are certainly disappointed! This picture is probably not for everyone though. In this page, we will discover the issue from some of the angles in order to learn from it and to incorporate the state-of-the-art methods and techniques for expansion of qanats, including the socio-economic environment of qanat.

Persian Qanat as a World Heritage

11 qanats in Iran, have been registered at UNESCO as one of the world heritages. The authenticity of the eleven qanats has been respected regarding design, technology, building materials, traditions, techniques, management systems as well as intangible heritage associations based on knowledge of the natural environment, material technology and the indigenous culture. Qanats have been founded and constructed based on social collaboration, communal trust and honesty as well as common sense. Furthermore, their stability and functionality have been managed, preserved, expanded and developed based on such joint cooperation. Two main criteria for this registration were as follows:

1) The Persian Qanat system is an exceptional testimony to the tradition of providing water to arid regions to support settlements. The technological and communal achievements of the qanats play a vital role of qanat in the formation of various civilizations. Its crucial importance for the larger arid region is expressed in the name of the desert plateau of Iran which is called “Qanat Civilization”. Dispersion of primary settlements on alluvial fans of the inner plateau and deserts of Iran is immediately related to the distribution pattern of the qanat system across the country. The system also presents an exceptional living cultural tradition of communal management of water resources.

2) The Persian Qanat system is an outstanding example of a technological ensemble illustrating significant stages in the history of human occupation of arid and semi-arid regions. Based on complex calculations and exceptional architectural qualities, water was collected and transported by mere gravity over long distances and these transport systems were maintained over centuries and, at times, millennia. The qanat system enabled settlements and agriculture but also inspired the creation of a desert-specific style of architecture and landscape involving not only the qanats themselves, but their associated structures, such as water reservoirs, mills, irrigation systems, and gardens.

Rationale

Cooperation in qanats can be seen from their construction to their maintenance and the management of the water conveyed. A qanat is a geographically extended system being sometimes tens of kilometers long. In fact a qanat gallery cuts through a variety of geological formations, runs beneath many human settlements and cultivated lands and is subject to numerous potential threats. Therefore a qanat cannot be built, maintained and operated just by an individual but it demands vast cooperation from the community. Moreover, the water conveyed by the qanat is shared by hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of users. In an arid region, such sharing of water requires enormous cooperation. And such cooperation is not possible without an efficient and equitable management of the water.

Hence from their construction to the last drop of water from its gallery, the qanat requires cooperation from all stakeholders. However such cooperation does not occur in a vacuum but rather is derived from and is consistent with society’s existing social institutions and values. Thus qanat water management, and the social cooperation it requires, reflects the society in which it exists. However, given the massive cooperation required for a qanat to be sustainable, it is also true that the qanat must develop new social institutions that, while consistent with existing social values and institutions, also extend and apply them to new areas of cooperation. And by so doing, the social institutions fostered by the qanat may also spread to the other realms of social life and thus becomes part of the social capital of that society.

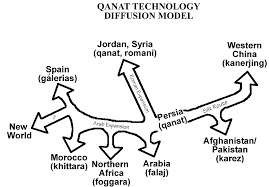

Not only has the qanat fostered cooperation within societies, but it has also fostered cooperation between societies. Throughout history qanat technology has crossed borders and cultures, taking with it a set of social institutions designed to resolve water conflict and promote the peaceful sharing of water. For example, approximately one thousand years ago Zobeydeh, the Abbasid caliph’s wife, dispatched a team of qanat workers from Iran to Mecca, in today’s Saudi Arabia, to build a qanat to quench the thirst of the Moslem pilgrims. Centuries earlier the Achaemenid kings had the Persian soldiers dig qanats in Egypt to extract groundwater where no surface water was available, leaving behind a technology and a heritage of cooperation. In the medieval times Moslems introduced qanat to the north of Africa and later to the south of Europe, which was brought to the new world by the European explorers centuries later. Thus qanat knowledge, and its associated culture, was transmitted from nation to nation in the course of history. The above examples from history demonstrate that qanats have been vehicles of cooperation between different nations and cultures, and thus helped pave the way for mutually beneficial interaction between them, rather than the type of conflict that has too often plagued history. In this sense, Qanat can are a symbol of international cooperation and the peaceful and sustainable sharing of a valuable resource. Thus, like the Olympic flame, qanat knowledge, and its associated culture, was handed from nation to nation.

The long and sustained physical and social success of qanats is impressive and is a testament to the social cooperation they have achieved within a culture. And this heritage of social cooperation has been exported all over the world, as Qanats can be found in more than 40 countries.

A Qanat is an underground channel used to transport water to the surface for irrigation and drinking which is environmentally sound water harvesting.

Qanta concept

the Ancient Water Tunnels Below Iran's Desert which is still in use.

a Cooperative Water Harvesting and Ecosystem Protection System in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions;

To use the “qanat” indigenous knowledge for sustainable management of land, water, and agricultural biodiversity through strong collaborative work among sustainable agricultural communities.

The importance and value of Qanat as a system that is getting life from the nature and giving it back in harmony with nature.

The overall cultural and social structure of Qanat Strategy can provide a concept and framework for optimising water and land use to ensure sustainable socio-economic development regionally at least in the middle east.

"Water Banking"

Rich technical and social concepts of qanat and water harvesting concepts & systems.

Improve awareness regarding water harvesting, climate change and food security issues.

Social structure to manage water rights, water distribution, and water markets

Lessons from qanat to solve water conflicts and promote peace and cooperation

The role of qanats in facilitating social cooperation and sustainable development

The influence of qanat social institutions on other elements of society

Ethical aspects of qanat water management

Role of qanat in rural economy

Environmental Management and Modelling with a focus on water harvesting, climate change and food security.

The current challenge in Iran: Water-wells and groundwater extraction

Like many countries in the region and world, Iran faces a severe water crisis due to climate change and poor water management.

Nowadays growing crops in Iran is mainly based on using non-renewable groundwater (overexploiting groundwater resources over the last decades, resulting in a steady decline of groundwater levels).

Most of the farmers’ share water from water-wells but this water is not enough to irrigate the farm so they are highly dependent on rain.

301,620 views Jun 5, 2017, Thousands of years ago, Persians created an ingenious system to provide water across their arid landscape. They tapped aquifers at the heads of valleys and designed tunnels that utilized gravity to send the water to settlements. It's now estimated that the combined length of all the underground channels, known as qanats, in Iran is equivalent to the distance between the Earth and the Moon (National Geographic).

BENEATH IRAN'S DUSTY DESERT LIE ANCIENT WATER TUNNELS STILL IN USE

BY RACHEL BROWN

• PUBLISHED MAY 31, 2017

• 4 MIN READ

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/iran-qanat-irrigation-engineering-history-video

From above, it seems as though a series of holes were pierced in the desert’s dry surface. But a hundred feet below the mysterious pits, a narrow tunnel carries water from a distant aquifer to farms and villages that wouldn’t exist without it.

These underground aqueducts, called qanats, are 3,000-year-old marvels of engineering, many of which are still in use throughout Iran. Beginning in the Iron Age, surveyors—having found an elevated source of water, usually at the head of a former river valley or even in a cave lake—would cut long, sloping tunnels from the water source to where it was needed.

The orderly holes still visible aboveground are air shafts, bored to release dust and provide oxygen to the workers who dug the qanats by hand, sometimes as far as forty miles. The tunnels eventually open at ground level to form vivid oases. (Watch: the secret history of saffron, the world's priciest spice.)

Constructing qanats was a painstaking task, made even more so by the need for great precision. The angle of the tunnel’s slope had to be steep enough to allow the water to flow freely without stagnating—but too steep and the water would flow with enough force to speed erosion and collapse the tunnel.

Although difficult work—even after completion, qanats require yearly maintenance—the irrigation tunnels allowed agriculture to bloom in the arid desert. The technology spread, through Silk Road trade and Muslim conquest, and qanats can be found as far as Morocco and Spain. (Read about the Persian legacy in modern Iran.)

For Komeil Soheili, an Iranian filmmaker who produced the video above, qanats are an integral part of the landscape of his native Khorasan Province.

“The diversity of landscapes and cultures [in Iran] is something that’s not well understood by the world,” Soheili says. “One of the oldest civilizations in the world came from this amazing creation, [the qanat.]” (See some of Iran's most wild and beautiful places.)

Gholamreza Nabipour, 102, is one of the last and almost certainly the oldest mirab, or caretaker of qanats. Recognized by the Iranian government as a national living treasure, Nabipour tries to share his craft with younger generations—including one of his sons, who uses a qanat to irrigate his pistachio farm—but fears for the future of this fragile tradition. (See Iran's centuries-old windmills in action.)

In the 1960s and 1970s, the subdivision of the large estates that relied on qanats caused an administrative tangle, and many qanats fell into disrepair without the traditional communal maintenance. And as modern agriculture takes root, Soheili explains, “people don't depend on qanats anymore, as it was before. It’s not possible to feed your family and earn money by working in qanats,” which have become less a way of life and more of a “hobby.”

In 2016, UNESCO listed the Persian qanats as a world heritage site.

“These qanats have been the source of life for me and all of my ancestors,” says Nabipour in the video. “It’s my duty to preserve them until the last second of my life.”

Indigenous Knowledge and Techniques of Runoff Harvesting (Bandsar and flood diversion), ICE REPOSITORIES, Ice houses, in Arid and Semi Arid Regions of Iran

Construction of ponds and other water reservoirs: storing water in reservoirs offers the flexibility of storing and conveying water

Links:

-Beneath Iran's Dusty Desert Lie Ancient Water Tunnels Still in Use | National Geographic: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8lS_ar5UpiU

At 102 years old, Gholamreza Nabipour is the oldest and most experienced caretaker of qanats. And while they are still in use today, Mr. Nabipour worries about the upkeep in the future. He has dedicated his life to training new caretakers on how to work and preserve the ancient life-giving tunnels.